We noted on October 20 how the proposed North Carolina Senate map tended to favor Republicans. We also noted how closely they adhered to or failed to adhere to traditional redistricting criteria:

The CPI indicates that there are 16 safe Democratic seats, 1 likely Democratic seat, 5 toss-up seats, 5 lean Republican seats, 4 likely Republican seats, and 19 safe Republican seats in the state Senate…

The Senate maps have a mean compactness score of 0.41 on the Reock test and 0.32 for the Polsby-Popper. The proposed map split municipalities a total of 42 times when accounting for county lines, and has a total of 11 precinct splits.

Our April report, “Limiting Gerrymandering in North Carolina,” provides information on traditional redistricting criteria and how they can be used to reduce gerrymandering. Among those criteria are keeping municipalities whole and making districts as compact as possible while adhering to other criteria.

Let’s look at two districts in the proposed Senate map and see how each fails to follow one or more of those criteria. All graphics are from the North Carolina General Assembly’s proposed Senate map.

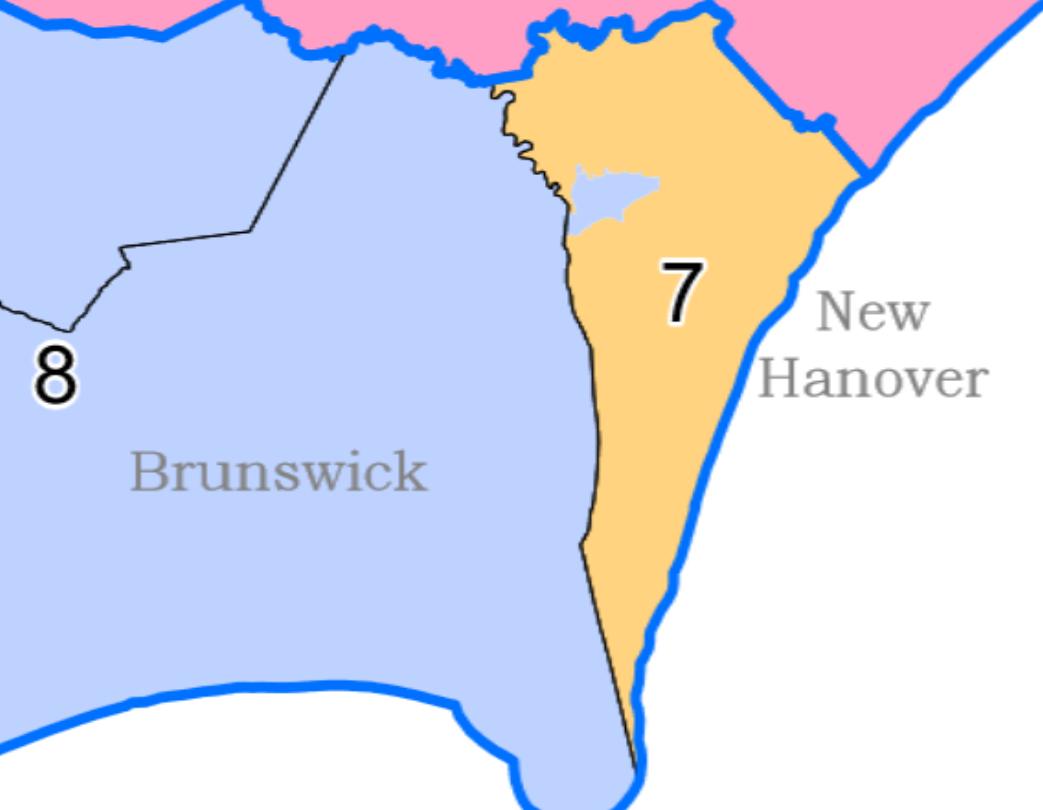

Problem 1: Splitting Downtown Wilmington

New Hanover is in a county cluster with Brunswick and Columbus counties. Since New Hanover’s population is too large for one Senate district, part of it must be joined in a district with the other two counties.

Legislators could have joined some northern New Hanover suburban precincts with the 8th District; That would have paired them with the Wilmington suburbs in northeastern Brunswick. They could have joined some of the beach towns of southern New Hanover with the 8th; that would have paired them with the beach towns of southern Brunswick.

Instead, legislators split off downtown Wilmington from the rest of the city and joined it to the 8th. While any map would have divided one or more municipalities, this version divides the area’s only urban core.

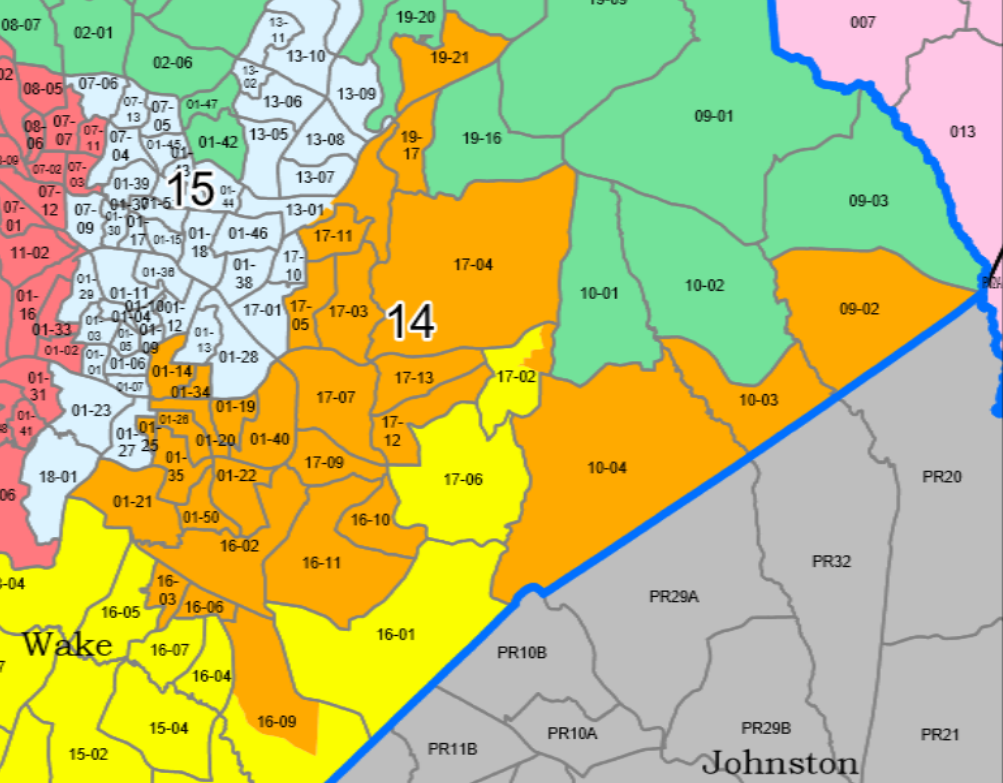

Problem 2: Ignoring Compactness (Or Dan Blue’s Isthmus)

Senator Dan Blue represents eastern Wake County, including eastern Raleigh. The proposed Senate map gives his 14th District a bit more of downtown Raleigh but takes away part of the district along the border with Johnston County. The cut is so deep that it nearly splits his district in half.

I would say that the district is held together by a single precinct, but that is not true. It is held together by part of one precinct. The proposed map splits Precinct 17-02 to hold the district together (The North Carolina constitution requires that “Each senate district shall at all times consist of contiguous territory.” At one point, the district is only the width of a single census block. Unsurprisingly, the district scores poorly on measures of compactness.

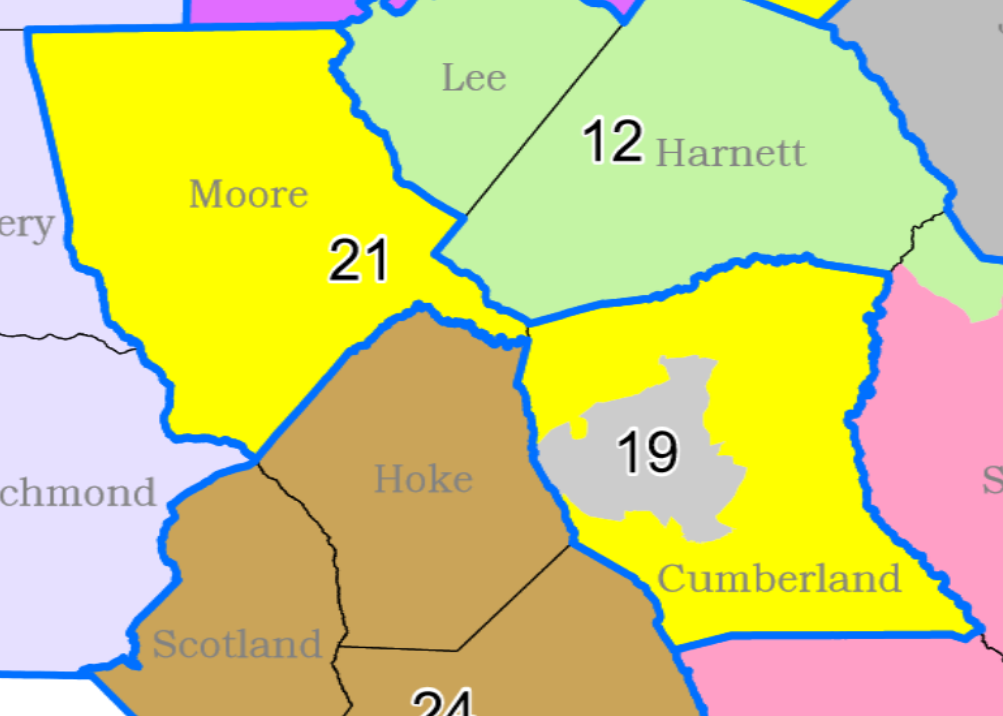

A Legitimate Reason for Looping Around Fayetteville

Another district appears to have the same compactness problem as Blue’s. Unlike Blue’s district, however, there is a legitimate non-political reason for drawing this district the way they do.

Districts 19 and 21 are part of the Cumberland-Moore county cluster (the Stephenson process legally requires those counties to be paired to make two districts).

While the 21st District scores just as poorly as the 14th on compacts, there is a reason for looping around the 19th: keeping Fayetteville whole. Balancing compactness with keeping municipalities intact is a redistricting dilemma I wrote about before the legislature drew districts in 2021:

The first option… would be to add the western half of Fayetteville to the 21st District with Moore County and join the eastern half of Fayetteville with rural areas of Cumberland County to form the 19th District. The districts would score an average of 0.3980 on the Reock compactness score (a 0–1 scale, with one being the most compact)…

The second option, depicted in Figure 4, would contain nearly all of Fayetteville in the 19th District. The more rural portions of eastern and southern Cumberland County would join Fort Bragg and Moore County in the 21st District. The districts average 0.3308 on the Reock compactness score, showing that this option creates less compact districts.

The 19th would be a solid Voting Rights Act (VRA) district, with 46.96% of the population Black and 63.39% nonwhite.

While it is hard to see a redistricting criterion other than partisanship for the New Hanover and Wake districts noted above, there are legitimate reasons for using criteria other than compactness in the Cumberland-Moore cluster.

So, when judging maps, we cannot always depend on appearances.