What should we value more when it comes to map drawing: that a district be drawn to represent a community of interest or which party may have an advantage in that district?

Philosophically speaking, a district should be drawn to give a geographic community a voice in their government. However, the process of map drawing has always been a political one, with all parties involved attempting to gain an advantage through the manipulation of lines. This is most evident in how both parties looked to split some of the state’s largest cities in congressional maps during redistricting in October.

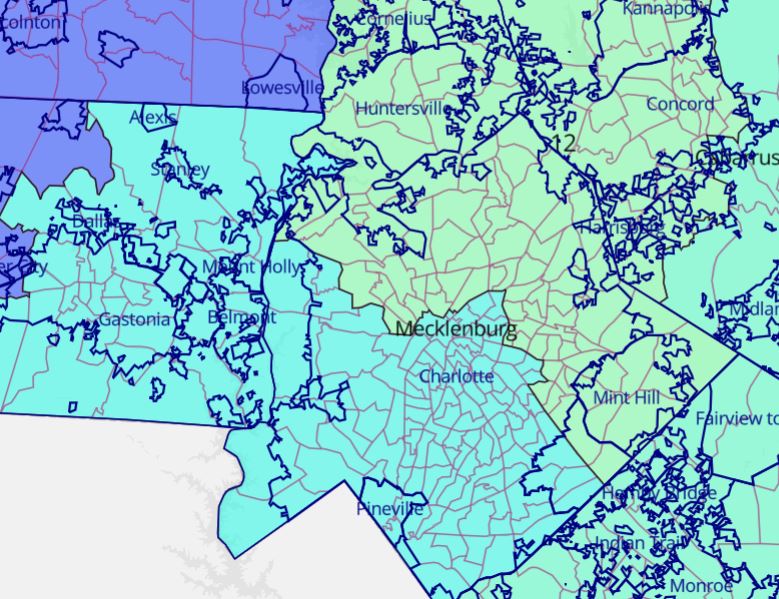

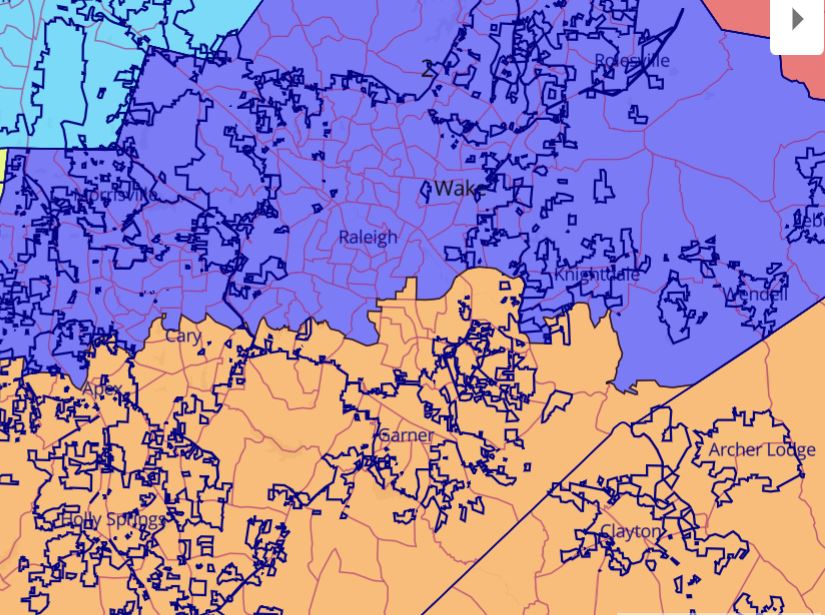

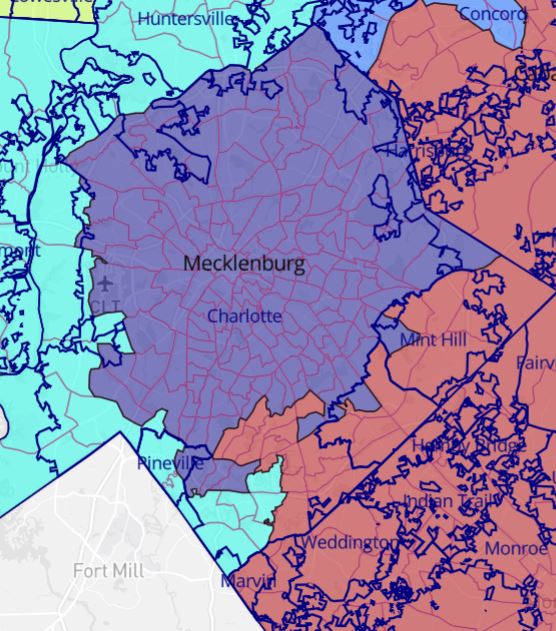

Democrats wished to maintain the court-drawn 2022 congressional map, which split the state’s two largest cities, creating a 7 Republican and 7 Democrat map. By bisecting Charlotte and combining the heavily democratic-leaning southeast portion of Raleigh into the district with Johnston and Harnett counties, they broke apart inherent communities of interest in those cities to create a more favorable map for Democrats than is likely to occur under neutral redistricting criteria.

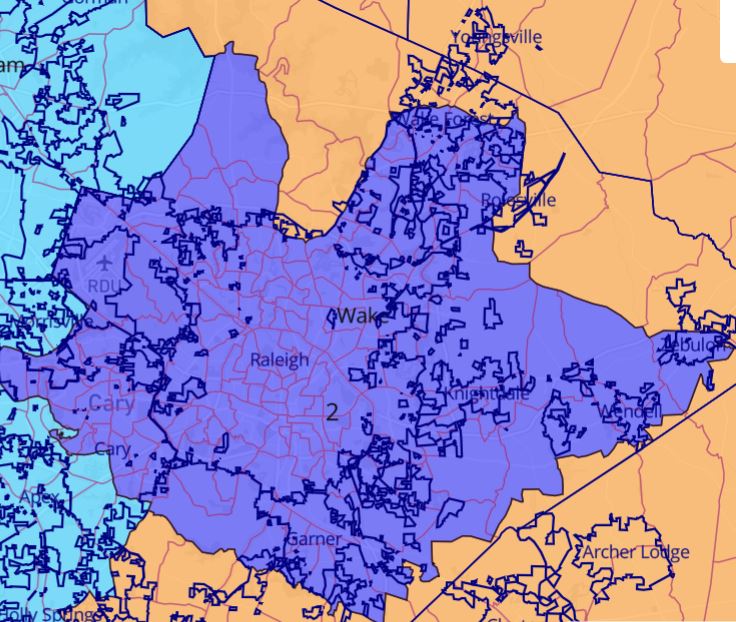

The Legislative Republican’s latest congressional map does a better job of keeping Raleigh and Charlotte whole. Raleigh is almost entirely kept whole within District 2, with only a small sliver of the northern part of the city inside precinct 02-06 being lopped into District 13.

The newest map also keeps the vast majority of Charlotte within one district, with only a handful of the southeastern precincts of the city excluded from congressional District 12. While this does a far better job at keeping Charlotte whole than the special masters maps from 2022, the map could have done a better job keeping Charlotte together. While Charlotte does exceed the population limit for a North Carolina congressional district, The Locke Foundations “Limiting gerrymandering” study showed that legislators could keep more of Charlotte whole while limiting the splitting of precincts by incorporating precincts that were wholly contained within the city.

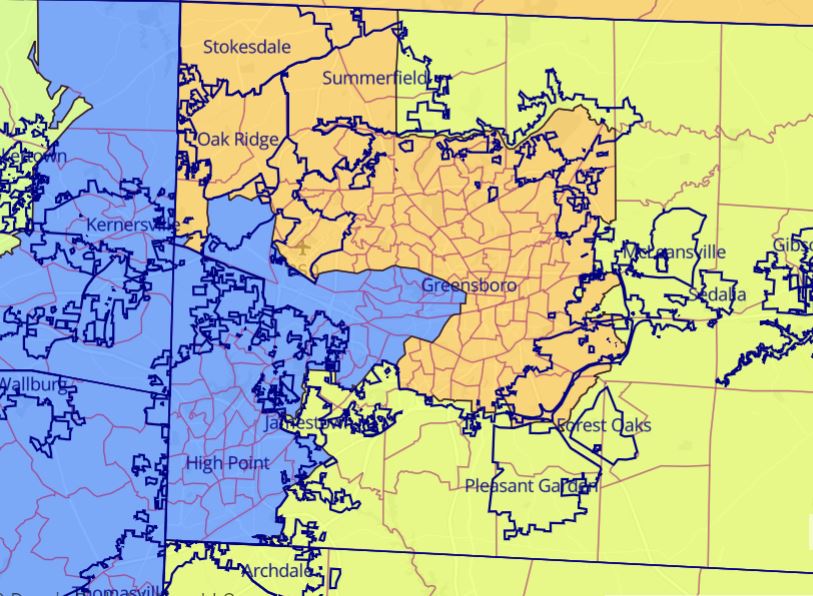

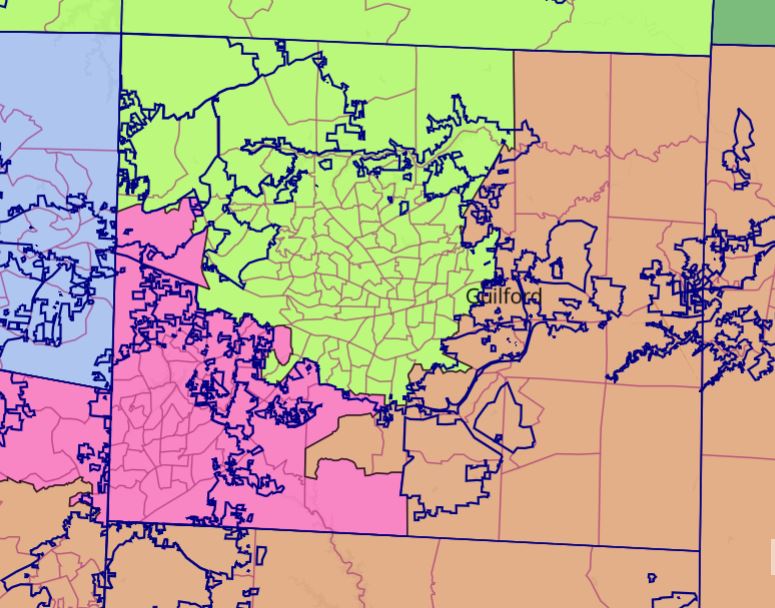

While Charlotte could still use improvements in the latest map, Republicans did a far better job keeping Charlotte and Raleigh whole than the prior maps. The problem with these new maps comes once we look at Guilford County, where Republicans chose to create a three-way split of Guilford County and slice off parts of central and southwest Greensboro into a separate district. This is an unnecessary division of the Greensboro electorate that map drawers could have easily kept together.

This is the second time Republicans have opted for a tri-split of Guilford County, having first attempted to do this in their original congressional map drawn in 2021. However, in the prior map, they at least kept the city of Greensboro mostly whole. The only exceptions to this were a few precincts that were split between being part of the city and unincorporated land along its eastern and southern borders.

One thing must be made clear: drawing congressional maps is difficult. A district’s population must be 745,671 people, with a leeway of only +/-1 person allowed. Even if we ignore all other criteria, this population requirement makes it nearly impossible for every municipality to be wholly contained in one district or another. That being said, those drawing congressional maps should still attempt to keep cities and municipalities whole whenever possible.

Both sides have excused their unnecessary divisions of cities as being a boon for the city. The more representatives it has, the better off the city will be in its representation of Congress. However, this argument is inherently flawed for North Carolina. No city in the state has a population that requires a majority of two or more districts to be built around its population. By bisecting a large city like the court-ordered map does with Charlotte while increasing Charlotte’s representation in Congress, it dilutes the voices of rural and suburban voters outside the Charlotte area. The opposite is also true in the Republican maps; by chopping away at Greensboro and dividing it into several more rural districts, you dilute the voice of that community of interest.

The most likely outcome under politically neutral redistricting criteria for North Carolina’s congressional maps district leanings is 9 Republican and 5 Democratic seats. Both a 7-7 and a 10-4 Republican-favored map, while possible, are highly unlikely. Yet we have been presented with these two results due to the insistence of both parties to divide major cities for political purposes. How we create maps should come before the results of the map.

Fair maps are not based on the likely political outcomes of districts but on a geographic community receiving a voice in their government.